Stay connected with BizTech Community—follow us on Instagram and Facebook for the latest news and reviews delivered straight to you.

The U.S. is dealing with a growing debt crisis that has Wall Street and other places on high alert again. In early 2025, the national debt will have grown to more than $36.5 trillion, and the debt-to-GDP ratio will have risen to 124%.

This means that worries about the long-term viability of America’s fiscal path are no longer limited to the periphery.

Hedge fund billionaires and former budget officials are among the most well-known voices in finance who are warning of a possible economic “heart attack” if things keep going the way they are.

The possibility of a disaster in the bond market is greater than ever if Washington moves on with its ambitious spending plans, such as the recently announced One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA).

But is the U.S. really about to go broke, or is this just another case of crying wolf?

The Increasing Debt Load

The U.S. national debt has grown to levels never seen before because of years of spending more than it has and recent legislative moves that made things worse.

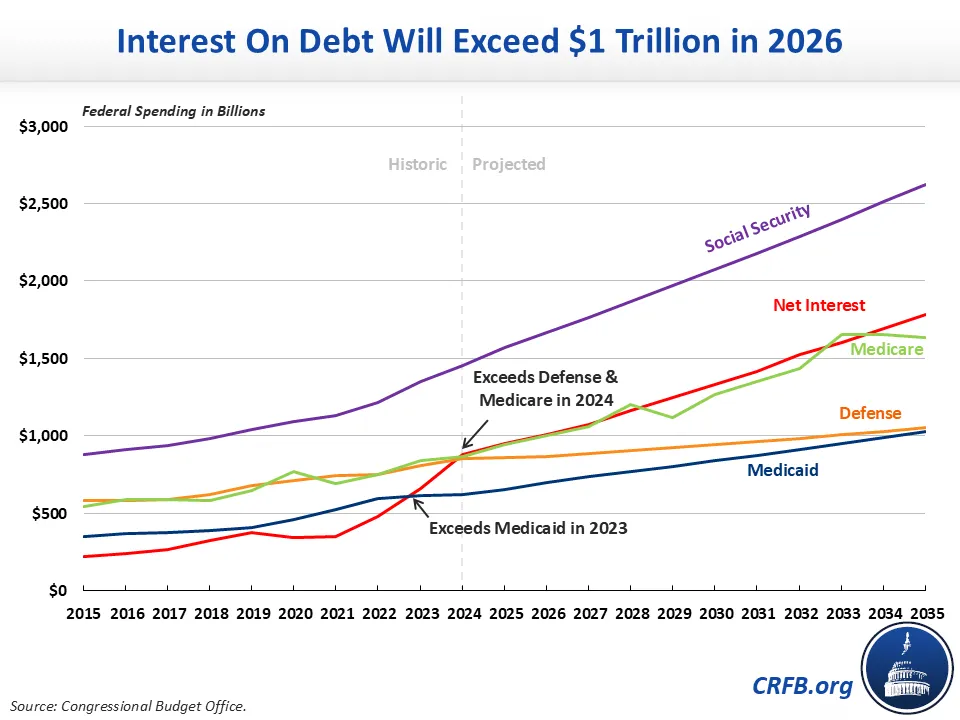

The cost of interest on the debt is now more than $1 trillion a year, which is more than the defence budget and the total cost of Medicaid, disability insurance, and food stamps. This number alone shows how big the problem is, since paying off the debt takes up more and more of the federal budget.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) says that the debt could reach $50 trillion by 2034 if current policies stay in place.

The OBBBA could add another $3 trillion over the next ten years, or $5 trillion if temporary provisions become permanent, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB).

These estimates are based on the idea that the bond market will be rather stable, with 10-year Treasury rates staying around 4.4%.

The CRFB, on the other hand, thinks that if yields stay high or go up even more, interest expenses will go up by another $1.8 trillion over the following ten years. In this case, rising yields could start a vicious cycle in which higher borrowing costs make the debt even bigger and make investors less confident.

Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan, recently warned that the bond market could “crack.” This shows how fragile the current financial situation is.

Voices of Warning

The chorus of worry is getting louder, and important people are ringing the alarm. Ray Dalio, a hedge fund manager, wrote the book How Countries Go Broke, which came out in June 2025.

He thinks that the U.S. has just three years to avoid a major economic crisis. Dalio’s warning isn’t based on book royalties; it’s based on a serious look at fiscal patterns.

He says that the combination of debt that is growing too fast, interest rates that are going up, and spending that is out of control might cause an economic “heart attack.”

Peter Orszag, the CEO of Lazard and a former director of the Office of Management and Budget, has also gone from being sceptical to being alarmed.

Orszag used to think that concerns about unsustainable deficits were overblown, but now he thinks the risks are far more real. He recently remarked, “The wolf is lurking much closer to our door,” pointing to the fact that the federal government is borrowing too much money.

Even Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who is trying to calm the markets by saying that the U.S. will never default, knows how serious the situation is. But default isn’t the only risk.

Rapid inflation, caused by fiscal dominance (when the Federal Reserve has to turn debt into money), might make the currency less valuable and make the economy less stable.

Kenneth Rogoff, a former head economist at the IMF, says that debt crises typically happen before arithmetic forces a breaking point. This is because of a loss of market confidence, not a specific tipping point.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act: A Point of Fiscal Conflict

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act is at the centre of the present controversy. Critics say that it might make the debt problem worse by cutting taxes and spending. The CRFB thinks that the OBBBA would add $3 trillion to the debt over the next ten years.

If the interim provisions are extended, the number may go up to $5 trillion. Nick Timiraos, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, says that this is happening at a time when the government deficit is already expected to stay “extremely large” for the foreseeable future.

People are worried that the economy will get too hot because the bill passed the House and there are plans for tariffs and tax cuts. People are worried that these policies could raise bond yields because foreign demand for U.S. debt is falling and inflation is rising. One user, @Akshay_Naheta, said that the OBBBA, along with tariffs and onshoring, might make people “lose trust” in U.S. bonds, which would make rates “explode.”

The Bond Market Paradox

Even with these warnings, the bond market hasn’t shown signs of full-blown panic yet. The yields on 30-year Treasury bonds just reached a post-crisis high, although they are still below levels that would mean a full-blown crisis.

Hedge fund manager Paul Tudor Jones calls this a “economic kayfabe,” which is a phrase from professional wrestling that means everyone is pretending to believe something. Investors are still putting money into the market, even though they know the debt situation is not sustainable. They are betting that the show will go on.

This contradiction poses an essential inquiry: Why are markets not responding more vigorously?

One reason is that the U.S. dollar is the world’s reserve currency and there isn’t a good alternative. Also, the fact that the Federal Reserve can step in gives the economy a short buffer. Rogoff says that debt crises typically happen quickly, not because of a set threshold but because of a change in mood.

Historical Background and Contemporary Risks

The story of the debt issue is not new. A big news magazine had a cover story in 1972 called “Is the U.S. Going Broke?”

It showed Uncle Sam with empty pockets. People at the time thought these kinds of warnings were alarming, and similar prophecies have often not come true, which is why opponents are called “perennial doomsayers.”

But the situation is different now. The debt-to-GDP ratio is now 124%, which is higher than what is considered sustainable. This means that interest payments are taking up more of the budget than other important things.

Tariffs and geopolitical conflicts from outside the country could also make things worse. Tariffs are supposed to help the domestic economy, but they are expected to raise inflation and delay growth, which will make the budgetary situation much worse. In June 2024, The Wall Street Journal said that these policies could make the economy worse, making it harder to deal with the debt.

The Way Ahead

To fix the debt situation, politicians will have to make tough decisions, like cutting spending and maybe raising taxes. These are things that have been hard to do in Washington.

People are getting more and more angry over the change from promises of fiscal restraint to hopeful statements that we can “grow our way out” of the debt.

Some people on X said that this kind of talk makes it sound like they are relying on growth assumptions that can’t last, like a “Ponzi mode.”

The CRFB and other experts say that we need to act right away to lower deficits and keep the debt-to-GDP ratio stable.

If these steps aren’t taken, the U.S. could end up in a situation where rising rates and inflation hurt the economy, leaving the Federal Reserve with no choice but to act. As Dalio and others have said, the time to act is running out, and if the tipping point is reached, the results might be very bad.

Final Thoughts

The U.S. debt crisis is no longer a distant threat; it is now a serious one. This is clear from the warnings of Wall Street experts like Ray Dalio, Peter Orszag, and Jamie Dimon.

The bond market hasn’t crashed yet, but the combination of high debt, rising interest rates, and irresponsible government spending might cause a crisis much sooner than predicted. Herb Stein, an economist, once observed, “If something can’t go on forever, it will stop.” The question is not if, but when, and if policymakers can act before the wolf at the door grows too big to ignore.